Human rights report: “In addition there is organized crime. In the last decade, more than 200 farmworkers have disappeared in this country without a trace.”

What does Wendy’s have to say about its produce partner of choice? Not a thing…

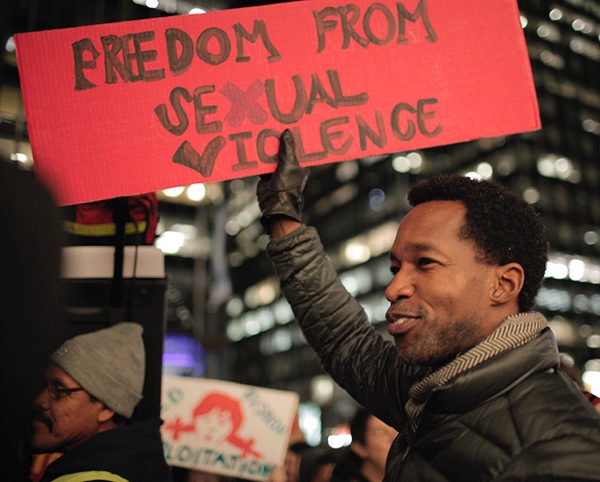

When the CIW announced its call for a national boycott of fast-food giant Wendy’s on March 5th, 2016, in New York City, Lupe Gonzalo declared:

“Wendy’s hasn’t only refused to sign an agreement with farmworkers here, they are trying to escape responsibility by buying tomatoes in Mexico where there is still exploitation, taking advantage of the poverty of those workers where there is still forced labor, sexual abuse, and child labor.”

That claim — of rampant, unchecked exploitation and abuse in Mexico’s produce fields — was based, in part, on the personal experience of farmworkers in Immokalee, a majority of whom are from Mexico and Guatemala and many of whom worked harvesting tomatoes, peppers, and other fruits and vegetables in Mexico’s agricultural industry before coming to Florida. It was also based on the excellent, in-depth reporting from the Los Angeles Times on the Mexican produce industry — in particular a hard-hitting investigative series titled “Product of Mexico: Hardship in Mexico’s fields, a bounty for US tables” — that was published just months before the boycott announcement.

But since that time, there has been scant reporting from Mexico on labor conditions in agriculture there. This silence is due to many factors, but chief among them is fear — the workers’ fear of what might happen if they were to complain (one report that did manage to make it out of the fields was the news that 80 farmworkers went missing earlier this year after lodging a complaint against their boss in Chihuahua), and the fear of journalists for their own safety if they were to dig too deeply into abuses on farms where organized crime often rules the fields.

What happens in Mexico’s fields stays in Mexico’s fields…

Indeed, one of the great attractions for unethical companies doing business with the Mexican produce industry is the near total lack of transparency. To paraphrase the old marketing tag line about Las Vegas, what happens in Mexico’s fields stays in Mexico’s fields.

There are, it would seem, two principal ways to manage the reputational harm that the revelation of human rights abuses in a company’s supply chain might cause for a retailer like Wendy’s, one ethical, the other not. One would be to join the Fair Food Program, where the vast majority of human rights abuses are prevented by the Program’s award-winning mix of worker education, a 24-hour complaint line, independent, in-depth audits, and market consequences for labor rights violations. Eliminate the human rights violations, and eliminate the risk of public relations crises.

The other would be to buy your produce from a source where abuse may continue unchecked, but the news of the abuse itself rarely, if ever, sees the light of day. Sexual violence against women, child labor, and modern-day slavery still happen, but are effectively without consequence, because the public outcries those abuses would normally provoke never materialize. Workers are afraid to report abusive conditions in the fields, reporters are afraid to undertake independent investigations, and silence rules the day.

Between those two starkly different paths, we know which route Wendy’s chose. After its longtime suppliers here in Florida joined with the CIW and 14 other major retailers (including all of Wendy’s key competitors in the fast-food industry) in the groundbreaking social responsibility partnership that is the Fair Food Program, Wendy’s pulled up stakes here and shifted its purchases to Mexico. And for some time now, the implicit wager behind that decision — that the unconscionable labor conditions there would remain under the media radar — has largely paid off.

Until now.

Univision report covers “state of terror” in the fields…

The latest report from Mexico’s fields finds the same abuses — forced labor, child labor, extreme poverty, unsafe working conditions — documented so powerfully in the 2014 LA Times series. Here are just a few of the more appalling excerpts from the transcript of the Univision report (the report itself is in Spanish, and we have embedded it in its entirety at the end of this post for those who do not require translation):

Jésica Zermeño, Univision: In Mexico’s fields, farmworkers live as if they were slaves every day…

… Reporter: “How old are you?”

Farmworker: “14… well, I’m about to turn 14. We come in around 5, and get into the fields around 7, and end around 1 or 2.”…

… Activists who have heard the testimony of farmworkers who live in a state of terror.

Activist from Guanajuato, Giovanna Battaglia (reading): “We did not have water. We had to gather rain water in order to bathe, and the bathrooms were just out there in rows without even a wall or curtain.”

Activist from San Luis de Potosi, Jesus Carmona: “They reported receiving a large bottle of about 2 liters to drink with dirty water. And they of course had to drink it, because there was nothing else.”…

… The network of Mexican farmworkers, here at a press conference, have documented the deaths of farmworkers that start with just a headache, because they have no kind of medical services. Moreover, they are forced to stay in the agricultural fields, working under threats that start at the beginning of their travel.”

Carmona: “They reported that they put the children on the truck, and then other people got up as well, and then they take all of their personal documents.”…

… Jesica Zermeño: Although there are not statistics, it is estimated that more than 1 million Mexicans are farmworkers that travel year after year to one of the states that produce products in order to work, and of that number, over 300,000 are children…

… Jesica Zermeño: In addition, there is organized crime. In the last decade, more than 200 farmworkers have disappeared from this country without a trace.

These findings are indeed shocking, but they are also painfully predictable.

Poverty, exploitation, human rights abuses, and violence have haunted Mexico’s fields for decades. These conditions existed a generation ago, they existed in 2014 when Richard Marosi of the Los Angeles Times traveled there to file his exhaustive report, they exist today, and they will exist years from now, too, unless something is finally done to radically transform Mexico’s produce industry.

What is to be done?…

The only way that conditions will improve for Mexico’s farmworkers is if the buyers of Mexican produce stop rewarding abusive Mexican growers with their business and start demanding more modern, more humane conditions from their Mexican produce suppliers. Period.

How can we be so sure? Because that’s exactly what happened in the one instance in modern agricultural history when an entire industry — the Florida tomato industry — reversed course and, in a matter of just a few years, went from “ground zero or modern-day slavery” to what has been described as “the best working environment in American agriculture.”

Before the Fair Food Program, many of the same conditions that exist in Mexico’s produce industry today — rampant sexual violence against women, forced labor, extreme violence, and poverty — existed in Florida’s tomato industry. And as in Mexico, the Florida industry resisted change tooth and nail. The Edward R. Murrow documentary “Harvest of Shame” shocked the nation on the day after Thanksgiving in 1960; Congress periodically held hearings into exploitation in Florida’s fields; and case after case of modern-day slavery hit the headlines in the 1990s and early 2000s, but the industry would not budge.

How was such stubborn resistance possible? Because business — i.e., the buyers themselves — never demanded reform, so business as usual was a perfectly reasonable response to all the exposés, lawsuits, and slavery prosecutions that advocates could muster.

But all that changed when the buyers — driven by consumer demand in the form of the Campaign for Fair Food — got involved. The history of the Campaign for Fair Food by now is well-documented, so we will be brief. (For a much more comprehensive analysis of the roots and creation of the Fair Food Program, be sure to check out the new book I Am Not a Tractor: How Florida Farmworkers Took on the Fast Food Giants and Won, by Susan Marquis). Here below is the path, streamlined for the purposes of this analysis, that the Florida tomato industry took toward its own radical transformation:

- Workers and consumers pressured buyers to take responsibility for labor abuses in their tomato supply chains.

- Buyers agreed to only purchase Florida tomatoes from growers who are in compliance with a human rights-based code of conduct.

- After much resistance, first one (Pacific Tomato Growers) then another major Florida grower (Lipman) embraced the code of conduct, providing an opportunity for buyers to shift their purchases to those growers, thereby rewarding compliance and penalizing recalcitrance.

- Within a month, virtually the entire Florida tomato industry agreed to comply with the code of conduct, because the remaining growers could not stand by and watch the purchases of some of the largest buyers of Florida tomatoes come off their books and shift to the two growers who joined first.

- Today, forced labor and sexual violence against women have been eliminated in Florida’s tomato fields, and lesser violations are quickly becoming a thing of the past.

Only when buyers finally agreed to stop looking the other way and condition their purchases on compliance with fundamental human rights — and only then when two major growers finally agreed to step up to those human rights standards — did the economic incentives line up in such a way that fair labor conditions, not violence and abuse, were rewarded here in Florida, and a more modern supply chain was able to flourish.

Mexican growers are no different from Florida growers when it comes to being rational economic actors. They too will respond accordingly when the economic incentives are aligned correctly — toward rewarding common humanity and punishing violence — just as they would if the issue at hand were food-borne illness rather than human rights. If Mexican tomato farms were exporting the e-coli bacterium, instead of poverty and abuse, on every tomato they sent to the United States, you can be sure that the major buyers here would shift their purchases to alternative sources, and Mexican growers would shift their resources toward cleaning up their operations ASAP. The Mexican produce industry would not fiercely fight food safety standards and insist on business as usual while business fled the country. They would fix the problem in order to keep their most important customers’ purchases.

And the good news for Mexican farmworkers? The Fair Food Program already exists! It provides a socially responsible and sustainable alternative to the abusive Mexican system. Just as happened in Florida when two major growers provided an option for buyers motivated by the Campaign for Fair Food to shift their purchases to companies compliant with basic human rights standards, transformation in Mexico will take place only when buyers begin to shift to the human rights-compliant Fair Food Program. That shift — or even just the credible threat of it — will almost instantly compel Mexico’s industry to abandon its recalcitrance and join the 21st century.

Which brings us back to Wendy’s…

Given the continuing violence and exploitation in Mexico’s fields, and the unprecedented success of the Fair Food Program in preventing those same problems in Florida, to abandon Florida growers because they joined the FFP and do business in Mexico instead is the very definition of unethical supply chain management. And that is exactly what Wendy’s has done.

But just as it did here in Florida, change in Mexico must begin with consumer pressure on brands like Wendy’s that insist on turning a blind eye to the sexual violence, forced labor, and other abuses there. Once that process begins, it cannot be stopped, because, ultimately, even the most stubborn of CEOs must bend to the will of the market.

It is only a question of when, not if.

We will close this post with the Univision report in its entirety. Even if Spanish is not one of your languages, the images alone are worth the two minutes it takes to watch the video: