CIW AT THE 2008 SLOW FOOD NATION GATHERING

photos by Scott Chernis

|

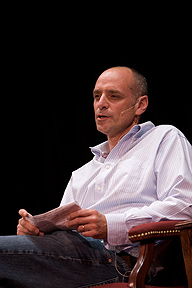

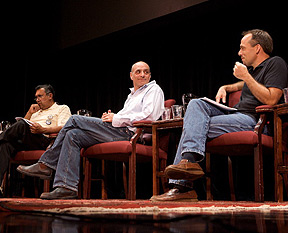

The CIW participated in one of the event’s keynote panels, shown here above, discussing the theme “Toward a New, Fair Food System,” as part of the gathering’s “Food for Thought” series. |

The panel was well-received among the Slow Food Nation activists, selling out the 900 seats of San Francisco’s historic Herbst Theater. |

|

Eric framed the discussion with one simple question: “Does it matter whether an heirloom tomato is local and organic if it was harvested with slave labor?” As it turned out, that question not only framed the day’s panel discussion, but captured the central tension at the heart of the Slow Food movement that ran beneath virtually all meaningful discussion at the gathering over the next several days. Eric’s Nation article, “Slow Food for Thought,” is a must read analysis of the movement, its conflicts, and its future. |

Greg’s presentation focused on the failure of the sustainable food movement as a whole to adequately address the exploitation of farm labor over the past thirty years, a period that has seen the growth of the sustainable food sector from a boutique market to a mainstream phenomenon (growing by 20% a year since the early 1990s, well ahead of growth rates for the rest of the food industry). During that same period, farmworker wages and working conditions have regressed. Tomato pickers in Immokalee, for example, picked tomatoes for 40 cents per bucket in 1980 yet earn only 45 cents for that same bucket today (just to keep pace with inflation, the 40-cent rate in 1980 would have to be roughly $1.10 today). And since 1997 alone, there have been seven prosecutions for farmworker slavery in Florida, with now 18 farm bosses behind bars on federal slavery charges and well over 1,000 workers freed from forced labor operations. Specifically, he pointed to a quotation attributed to Chipotle CEO Steve Ells — “We decided long ago that we didn’t want Chipotle’s success to be tied to the exploitation of animals, farmers, or the environment” — to illustrate the moral poverty of a vision for sustainable agriculture that concerns itself with everything on the farm except the human beings whose labor makes the farm economy possible. He called on Chipotle to complete Ells’s otherwise laudable sentence (and for any Chipotle execs out there listening, the word you’re looking for is “farmworkers”…) , and on the audience of sustainable food activists to demand that Chipotle live out the true meaning of its its marketing slogan “Food with Integrity.” |

|

Lucas ended his presentation with something of a surprise announcement, breaking the news of the very latest advance in the battle for fair food: Whole Foods and the CIW had effectively wrapped up negotiations that very day on a landmark agreement! He explained that the agreement with Whole Foods is not only the first agreement of its kind in the supermarket industry but that, in working with Whole Foods Market, the CIW has the opportunity to truly raise the bar to establish and ensure modern day labor standards and conditions in Florida. And of particular interest to the audience of sustainable food activists, Lucas made clear the challenge that the Whole Foods agreement represents to other retail food leaders that market their food under the banner of sustainability. |

At its worst, Slow Food Nation 2008 was wrapped in a disconcerting mist of surreality, which seemed to hang especially thick around the gourmet food pavilion that was erected for the event (the “Taste Pavilion,” a display from which is pictured above, along with a wider shot, below left). To be there was to feel as if you had dropped in on Marie Antoinette and a gathering of royals plotting the revolution… |

An extensive excerpt from Eric Schlosser’s piece, “Slow Food for Thought,” captures the origins of the movement and confronts the friction between its stated social goals and its intense focus on delicious and lavishly prepared food, which is ultimately a pleasure accessible only to a privileged few: “The idea of slow food has its origins in the Northern Italian counterculture of the 1970s. While American hippies were forming communes and going back to the land, some of their socialist counterparts in Italy were embracing the traditional music, food and agriculture of life in the rural Piedmont region. Carlo Petrini, a brilliant and charismatic journalist, became the leading spokesman for the notion that there is nothing contradictory about championing pleasure and working for change. After staging a protest at a new McDonald’s near Rome’s Spanish Steps, Petrini and his allies issued a Slow Food Manifesto in 1987. “We are enslaved by speed,” it declared, “and have all succumbed to the same insidious virus: Fast Life.” Two years later, the manifesto was endorsed by delegates from fifteen countries, as the destructiveness of a mechanized, industrialized food system became increasingly clear. Today, Slow Food International has about 85,000 members in more than 100 countries.” The article continues: “At the heart of Petrini’s Slow Food philosophy is a set of fundamental values that aim to distance its celebration of pleasure from mindless decadence. According to the Slow Food trinity, food must be “good, clean, and fair.” The “good” refers to taste; the “clean,” to local, organic, sustainable means of production; and “fair,” to a system committed to social justice…” Schlosser concludes: “… The first Slow Food Nation partly fulfilled (this) broad agenda. It earned high marks for the good and the clean but next time could do a hell of a lot better with the fair. At the moment, the majority of Americans–ordinary working people, the poor, people of color–do not have a seat at this table. The movement for sustainable agriculture has to reckon with the simple fact that it will never be sustainable without these people. Indeed, without them it runs the risk of degenerating into a hedonistic narcissism for the few.” |

The Slow Food movement can no longer ignore the contradiction at the heart of its cause. “Ignore,” however, may be too strong a word. The SFN 2008 gathering did recognize the contradiction — through several keynote panel discussions and workshops, and surely thousands of side conversations throughout the weekend — but the mix between “championing pleasure and working for change” was still short of satisfactory. A pavilion dedicated to celebrating and supporting social change movements, for example, would have been a welcome balance to the over-the-top Taste Pavilion. A better mix the next time will send the message that change is not just an afterthought. It would be too easy, however, to take the cynical perspective that decries the obvious contradiction and stops there. Truth be told, the CIW benefited greatly from the opportunity to share our struggle with tens of thousands of food activists who care deeply about the origins of their food, and our delegation came away from the gathering with a far more profound understanding of the sustainable food movement — and the challenges faced by the movement across the globe — than ever before. For such a relatively young organization, Slow Food Nation has managed to carve out a valuable niche in that broader movement. Leaders of Slow Food Nation and many of its adherents enjoy a tremendous amount of resources and access to the media and policy makers, as demonstrated by the vast coverage of the San Francisco gathering, including features in the New York Times, the Washington Post, and Time Magazine. Those political, financial and media resources could do wonders for the multitude of grassroots “fair food” efforts — like the Campaign for Fair Food — spearheaded by community-based groups in poor communities across the country and across the globe that have had little voice in the movement to this point. The CIW was there, but we were one of only a handful of community/labor organizations present at an event where dozens, if not hundreds, of such organizations should have been involved and should have been heard. The public platform that the early leaders of the Slow Food movement have built is impressive. It is time, now, however, for those leaders to make more room on that platform for people from the communities that produce the world’s food — from farmworker movements in Immokalee to peasant movements in India — to seek out stronger and deeper partnerships with those popular movements and direct more of those resources toward their advancement. The good news is, the Slow Food gathering and its leadership gave every indication that they understand the criticism and intend to do just that. One can only hope that they also understand the urgency of that change, an urgency that is all too familiar to the laborers behind our food. |